Summary: The enormous size of the Chinese market does not mean that it is easy for western brands to penetrate. China is the kingdom of business and its customs are rapidly evolving. Its local players are well-versed in extracting the best from foreign innovations, though there are major logistic challenges to overcome in the e-commerce sector. Western brands must therefore invest and adapt to local conditions, while guarding their creativity and originality in the hope of establishing a foothold in this ultra-competitive market.

I recently attended an excellent one day conference on the development of the digital media in China organised by the Benchmark Group. Most of the numerous speakers (Ubifrance, Nurun China, Ifop Asia, Atelier BNP Paribas Group Asia, Lacoste, China Diligence, Reflex Shanghaï, 2K China, E-luxury brands, Accor, Viadeo, Orange Business Services, IP Label, Shopdescreateurs.com, Feeloë consulting) had had several years of professional experience in China, which allowed competing points of view to be expressed, and generated an interesting discussion for the less initiated among us. So here is a completely personal digest of the information and key ideas which I have taken from it, which can be summarised in 4 overarching points:

1. The figures are inevitably vast, which therefore requires a sense of perspective.

2. The Chinese are human beings like any others, with specific behaviours and customs: old stereotypes die hard!

3. China is the kingdom of business, with markets developing at full tilt and major local players who are well-versed in extracting the best from foreign innovations, though they have significant logistic challenges to overcome.

4. Foreign businesses must bring real added value in comparison to the locally available products and competencies if they are to hope to establish a foothold and subsequently develop there.

1. The figures are inevitably vast, which therefore requires a sense of perspective

China is a country of vast scale. None of the presentations spared us the avalanche of statistics which seem necessary to obtain perspective.

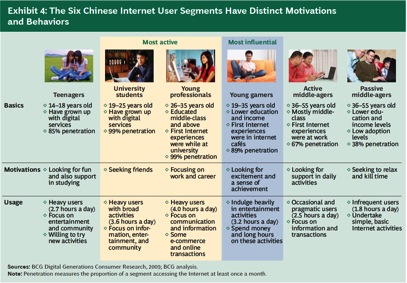

Lacoste’s Shanghai marketing manager made a useful comparison that enables one to begin to grasp the enormous scale of the Chinese mainland: imagine a country that spreads from Denmark to Niger, and from Brittany to Moscow. Though pay is currently low, the Chinese middle classes will number 850 million people in 2030, and there are already five times more millionaires there than in France (1.1 million millionaires according to a BCG study, with continuing sustained growth and unshakeable consumer confidence. All this should not conceal the extraordinary cultural and geographical diversity of the country, and the considerable differences in behaviour between the generations. Compared with those aged 45 and older, who experienced the communist period and the onset of the country’s capitalist development, the younger generation are consumerist, hedonistic, and confident of the future, feelings that are reinforced by their country’s growth. They are also torn between the two opposing poles of westernisation on one hand, and pride in being Chinese on the other. Everything is moving very fast in China now, and in response to urban growth, one can also see the appearance of inverse movements, such as, for example the migration of many people from « tier 1 » cities towards « tier 2 » cities, in search of a better quality of life.

Internet service is well developed, if patchy, in China, with two principal service providers splitting provision between the north and the south of the country, and significant differences in available bandwidth between the large cities and the rest of the country. According to IP Label, the average download time for a webpage in China is 8 to 10 seconds, in comparison with 2 seconds in Europe. This has significant consequences for website design, and explains the density of text and content found on the homepages of Chinese websites, which allows maximal access to information very rapidly. International bandwidth is highly regulated and all such traffic must pass through either Beijing or Shanghai, which considerably slows downloads from sites on foreign servers. In Hong Kong, where overseas web and mobile players are permitted, the iPhone has very high market penetration, as do Facebook and Twitter. The latter are however forbidden on the Chinese mainland, and it is the big local players who share the market, occupying similar market positions to their American counterparts: Baidu is the Google equivalent, Sina Weibo (a mix of Facebook and Twitter) is the most popular Chinese social network, Tencent is another major social player which owns QQ (IM), TaoBao is similar to eBay (70% of e-commerce, 2% of retail), Alipay its PayPal (>1.5 billion RMB of transactions/day), Tudou its YouTube, and, in March 2011, there are already more than 4,000 group purchasing sites comparable to Groupon.

As the technology was already sophisticated when it arrived in China, its adoption has been massive and intensive, notably in the mobile sector. Its utilization is already highly developed, even if all Chinese internet users are not born free and equal. IT equipment is not always state of the art, and software is often pirated, which limits updates and the use of Flash, large file sizes and HTML5. Internet Explorer 6 is the still the most popular browser.

For many, internet access is obtained in massive cybercafés hosting an average of 400 PCs! Though there were 130,000 of these cybercafés in 2010, they are now in the sights of the authorities, who have closed 100,000 illegal ones in recent years, as part of an official campaign against pornography and violence on the internet.

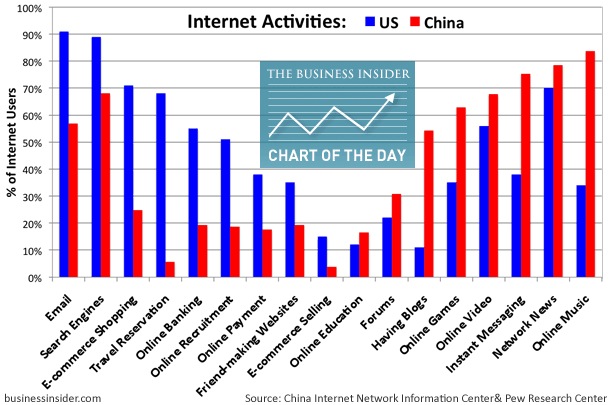

The number of Chinese internet users in 2010 is estimated to be 457 million (35% of the population), an increase of 19% compared with the previous year, which is more than 300,000 new users per day. Internet usage is intensive, with the average daily time spent on the internet twice that of the Europeans and Americans. Usage is varied: blogs, IM (instant messaging), social networks (235 million users, which is 18% of the population) and e-commerce (>100 million online users, around 8% of the population in 2009 according to Goldman-Sachs). These figures are already very impressive, but when one considers them in relation to the entire population, they are far from fully developed, and one can only wonder at the progress yet to come.

2. The Chinese are human beings like any others, with specific behaviours and customs: old stereotypes die hard!

Though the abstract national statistics unveiled are perhaps as hypotising as they are alarming, happily the practical observations reveal that the Chinese are, when all’s said and done, human beings like the rest of us–one is almost surprised to say it!

It may be pushing it a bit to say that Canton is the workhorse where the work ethic is king and price the key factor in consumer decisions, Shanghai the city of showoffs parading style over substance, and Beijing the capital of the chattering classes and tribes of well-connected yuppies, but the big cities are not all alike.

The universities have always played an important role in the social fabric it seems. It is there that couples meet and seek work, but the media traditionally associated with urban leisure in the West—radio, press, magazines—are relatively undeveloped, which explains the Chinese obsession for the internet. According to McKinsey, it is the internet that is filling the leisure hours of the inhabitants of China’s 60 largest cities, who pass 70% of their free time online! This could have a « seismic » impact on consumption in the years to come, say McKinsey.

Another social factor that cannot be ignored in this excessive internet use: the offspring of the one child policy, who find themselves alone in the presence of 6 adults (parents, two sets of grandparents) in the average family household. These only children are subjected to very high expectations of academic success, which requires many hours of private study at the weekend. Mobile platforms and social networks are an escape route from this pressure, and places to find friends and social interaction. More widely, the Internet is a venue for escapism, providing a growing number of Chinese people with the opportunity to live out experiences that they do not have in the real world, where they can blow off steam, and where verbal violence is not uncommon. This space of (relative) liberty allows the sensation of greater power in comparison with the pressures of real life.

Email use is relatively limited in China, but instant messaging, blogs and social networks are highly developed and dynamic, which makes them an obligatory part of any communication campaign. Among the examples cited by the speakers were Nurun, which is in the process of launching the Dukan regime in China using a strategy that is 100% digital, and Seat which is using social networks to increase its profile. The Chinese like to crosscheck the information with which they are supplied. The websites of brands therefore serve as guarantors of this information, but they are not the prime engines of raising brand awareness.

The Chinese are very extraverted and love to explain and share their opinions, posting, for example, many photographs of themselves online, and love clubs, privileges, and social circles. Politics is discussed on the network using a coded language that evades the filters of the censor. Contrary to received ideas, consumers do not want necessarily to buy fake brands, and the shopping malls are as much a place for a sociable stroll as they are destinations at which to make purchases.

3. China is the kingdom of business, with markets developing at full tilt and major local players who are well-versed in extracting the best from foreign innovations, though there are significant logistic challenges to overcome.

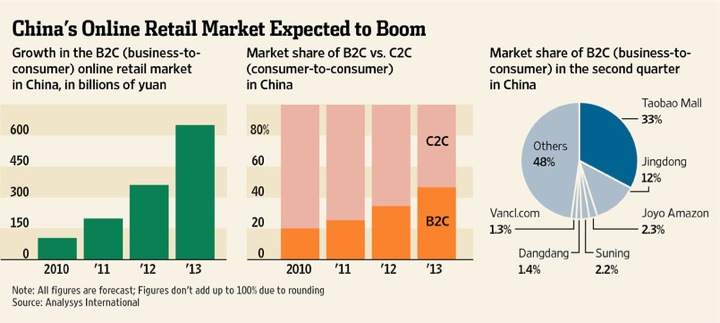

E-commerce in China is for the time being essentially a place for transactions between consumers. 92% of transactions are CtoC, with almost as many sellers as buyers. More than 100 million people, each with a modest commercial space online, sell on TaoBao, transacting among themselves. In order to guarantee trust in these transactions, the practice of escrow is widespread: an intermediary service accepts the money for a transaction from one of the parties, then sends it to the other once the transaction has been actioned. According to one of the speakers, Amazon is not as successful in China, because it has failed to understand the mentality of the Chinese in relation to their commercial practices.

What do the Chinese buy online? In decreasing order of sales volume: clothing, jewellery and fashion accessories, perfumes and cosmetics, computers and prepaid telephone cards, books, electronic equipment and telephones. CDs and DVDs are leading sellers in France, but rather take last place in China, being easily available for next to nothing. In every sector, discounting is an important trend, and counterfeiting a persistent feature, which is inevitably problematic for foreign brands. The Chinese online market is a source of great confusion because of the enormous quantity and density of information, and a profusion of counterfeited products abound: fake products, fake shops, for example fake Apple Stores (which sell the real thing) to genuine products bought abroad in parallel markets.

Though the Internet is a well-used source of information to find out about promotions and discounts, the rate of conversion of traffic to actual sales is still less than 1% at this time, and the average shopping basket is worth about 20-30 euros.

As in the west, specific e-commerce platforms are developing, such as weibo-commerce’s w-commerce (equivalent to the f-commerce = Facebook commerce), where product catalogues are increasingly integrated, which therefore increases sales. Many Chinese and foreign celebrities have their own weibo page (Tom Cruise, Bill Gates, and Christine Lagarde have all opened one), but as on Facebook, the conversion of a « follower » to a buyer is a challenge, and is certainly not a linear process.

M-commerce is also developing, positioning itself as the missing link between shops and home buyers, which suggests a significant active commercial role for shops in the future.

Among the players, TaoBao is the ultra-dominant and unavoidable site, both in CtoC and mass counterfeiting. A hundred or so results appear there following a search for Lacoste for example, almost all counterfeit, or at best, authentic products derived from parallel markets. TaoBao has developed a BtoB platform, Tmall, that allows brands to sell their original products, which is the almost obligatory first step for any foreign brand which wishes to develop e-commerce in China. Two examples for illustration: Gap, which launched without TaoBao, but then found it had no other choice but to open a boutique there subsequently, and by contrast, Uniqlo, which opened its boutique in the TaoBao Mall in May 2009 and now receives more than 700,000 visitors, 6,000 transactions, and $80k sales each day, equalling the performance of its 42 shops in China! The best e-commerce strategy for foreign brands is therefore to start with Tmall which will capture the most important traffic, with the objective of learning and establishing a foothold, and then to develop their own sites. This has been the strategy of Puma and Decathlon, present in China since 2009, but only now launching their own sites.

Some other notable players: Paipai.com (QQ/Tencent), TaoBao’s CtoC challenger, is the world’s fastest growing website, but exerts little scrutiny on the products sold there. On Sina, genuine luxury products are available, but they come from the parallel markets, and product images are used without the permission of the brands. Xiu.com serves only as a parallel market for luxury brands; it has recently raised lots of funding, and has hired an army of personnel who buy bags in Hong Kong every day then take them to Shenzhen to sell!

Online payment for small amounts is widespread. Everyone uses the PayPal equivalent Alipay. Cash payment is common for large sums, which means the costs of logistics and security are significant for luxury brands who want cash on delivery for their product.

As the exposition above has outlined, social networks and viral marketing are an important tool for recruitment to online business, and extreme competitive practices have developed there. For example, « snipers for hire » are used to propagate falsely negative comments on the websites of competitors. These libels are not generally resolved in the Chinese courts. The only solution for a business is to counter-attack using the same weapons as its adversary, by acquiring firepower for moderators, and posting positive comments that drown out the negative opinions. Unfortunately for foreign brands not so armed, and not culturally equipped to manage this welter of blistering comment, a vicious circle can quickly form that rapidly turns to disaster. The example of King Jouet is well-known—it was forced to close its doors in China after an experience of this kind.

Besides these very aggressive competitive practices, Chinese e-commerce has numerous problems linked to the abundance of available goods offered on the one hand, and the customs of clients and the organisation of distribution on the other. Problems with logistics and delivery are a source of complaint from consumers just about everywhere apart from Shanghai. Fraud is a concern, as is the desire for authentic, quality-controlled products identical to those which have been displayed online. Back office and logistic challenges are the major issues that must be overcome in the coming years if the pace of consumer demand is to be matched.

4. Foreign businesses must bring real added value in comparison to the locally available products and competencies if they are to hope to establish a foothold and subsequently develop there.

The Chinese market presents many difficulties for foreign brands. Adapting to these customs and local constraints is an absolute necessity if they are to hope to become established and develop there.

The basic difficulty is linked to the enormity of the market, and the impossibility of controlling all the sources of products sold and the images used (counterfeiting etc). There is nonetheless a real desire for these brands from Chinese consumers to be uncovered, and a true bonus of novelty for those who know how to exploit their niche, and bring original content and quality that does not exist locally.

The establishment and management of a foreign business in China are also a source of recurrent problems to handle, notably because of extremely significant employee turnover which is linked to rapid growth. Employees can be found—and lost—in a day. From this comes the importance of mixed management and the understanding of local customs rather than importing French or western practices which will be interpreted in a a completely different manner by the Chinese employees (for example, the way in which the boss exerts authority).

In consequence, and in contrast to western markets where online activity is considered as a complementary to traditional commerce by the majority of brands and distributors, e-commerce is the most rapid and economic means of accessing Chinese markets, and observing their operation before more substantial long term investments are made in bricks and mortar and paper-based communications. This does not mean that producing a Chinese version of a French or western brand’s website that is hosted abroad will suffice for success in China!

Some elementary rules must be respected for a good start to an online strategy in China. In addition to the various points already made, as the experiences shared by Accor, Viadeo, 2K and Yangjiu.com (a site that sells high quality wine from the west online) make clear:

– Having a .cn site (which must therefore be hosted in China) in Mandarin (at least), to allow rapid access to its pages is a must—or the site will be considered « broken. » Download times as long as 60 seconds for a luxury brand’s frontpage hosted abroad have been recorded; the average time is 17.5 seconds. An average of 47.8 seconds has been recorded on a French academic website! It is important to know that traffic destined for the European Union is routed via the US, so this may therefore be an intermediate solution for hosting before installing a Chinese server.

– Web design must be adapted to consumer taste, which prefers pages rich in text, images and colours, and is little used to minimalist design. To date, few foreign brands have sites in Chinese or hosting in China. Among those that do are DKNY and Ralph Lauren. Accor.com, whose a site has a western look and feel, has had little success until now compared with its online reservation competitor Ctrip.com. Ctrip maintains two very different versions of its site depending on the user’s language. The English version is stripped down to western tastes, while the Chinese version has dense content, with lots of text and colours.

– Avoid reservation « tunnels » that are too long. Three steps are the most that will be tolerated by the Chinese, compared with France where up to 6 are acceptable, according to Accor.

– Do not stint on technical investment. More backup servers are needed, in several locations, compared with the infrastructure that would be necessary in France for the same site. Database management is very complicated. There are only about fifty family names in the whole of China! The range of first names is also limited considering the size of the population, email is little used and/or the multiple contact addresses are common. Contacting a particular client therefore requires cross-referencing several pieces of information in the database: the name represented in Chinese characters, an email or IM address, a physical address, and a mobile number.

– The economic models must also be adapted to customs and according to the level of maturity of the market, as the experience of Viadeo and games editor 2k makes clear. The Chinese version of Viadeo, Tianji.com, has 8 million members in China. By way of comparison, Viadeo has 5 million members in France and 40 million in the entire world. In France, 50% of revenue comes from Premium accounts, which does not transpose to China, where the business model is for now based on advertising and paid services for human resource managers.

In the online games market, local practices are developing in games of western origin: for example in the Chinese version of Farmville it is possible to steal your neighbour’s harvest, which has given rise to the development of enhanced functionality that enriches the game (guard dogs, security services etc). Chinese editors don’t seek to « educate » the consumer, and have no particular marketing convictions in relation to their products. However they are very attentive to demand, and continually adapt their product to the expectations of their customers, which makes them excellent « optimizers » of foreign innovations for their local market, but with limited original creativity. This behaviour can be a source of inspiration for western brands, enabling promising developments that can be adapted to the tastes and customs of Chinese consumers.

In conclusion, China is certainly a gigantic market which still has immense potential for growth, but it is also a market which must be tackled in the face of considerable internal issues. Merely being of western origin does not give automatic credibility to a foreign brand. Observation of the market and understanding its customs, a capacity to adapt to local practices, and collaboration with local partners are all indispensible if one hopes to succeed there. The prospect of the conquest of the largest single market in the world (!) may merit the trouble and necessary investment, but serious study will be required before the venture is launched.

Translated from French by Douglas Carnall, Cabinet Beezer.